The Hidden Cost of Our Running Gear

Introduction

As trail runners, we view ourselves as stewards of the Earth, spending countless hours immersed in nature, running through desert, woodland, coastlines, and mountains. We are one with the natural world around us. Indeed, we comprise a critical fabric in the web of nature, though too often in the Global North (includes North America and Europe), we tend to forget that through our choices, we are weaving something much larger than ourselves. But the paths we forge through the natural world as a society are inextricably interwoven with the paths of our brethren in the Global South (includes Asia, Africa, and South America)… Here, we’ve come to expect an endless supply of colors and sizes and reasonable prices while there, the rivers run green or red or blue seven days of the week.

No doubt we arrive into this world naked, so as trail runners we need clothing, shoes, and other gear to aid us on our travels, as they serve to cover our bodies, protect our feet, and carry our nutrition. For tens of thousands of years, our ancestors produced only the clothing they needed and did so by hand, using materials sourced directly from the natural world around them – without much processing of these raw materials. Have you ever stopped to look at the labels on your clothing, shoes, and gear? Have you ever read the names of the countries where these were made, or understood the types of fabric used and how they were produced? Have you thought about the many sets of hands that touched your gear from inception to completion, what compensation those hands may have received, and what their daily lives and environment may be like?

Have you ever taken a moment to look more closely at your closet full of unworn race shirts and considered their origins as well? A shirt from your local 5K feels very local, but its label will confirm it has its roots in a factory on the other side of the world. Who originally converted the plastics into polyester threads, who aided the machines that spun them into cloth, who dyed them, and who later sewed them into tens of thousands of polyester shirts?

And why don’t more people even wear their hard-earned race shirts? Or opt out…

In this article, I explore a few countries around the world that produce much of what we wear on a daily basis. I also address the challenges of race shirts, running shoes, and what really happens to clothing at the end of its life. Finally, I discuss the greenwashing that seeks to distract us from the true life cycle of each garment, as well as the lack of circularity in the industry that produces them. I tend to believe that not all companies are guilty of greenwashing, but I also believe it is important to go beyond what your favorite retailer is saying to you, to understand what is actually occurring behind the scenes and whether the two messages are consistent.

I’m not here to point fingers at any one company (they’re all guilty), I’m not here to point fingers at athletes who love clothes or truly enjoy their race shirts, and I recognize that at least a few readers will turn away for something that emphasizes “happy trails” a little more. I get it. It’s a difficult topic to explore because many simply don’t want to hear about it, and it forces me to face the poor choices I’ve also made over the course of a decade head on. But we all need to know just how significantly our personal choices impact the land and water, upon which others far away so heavily depend day after day. If we truly are stewards of the Earth, then we should know the truths of how “environment” everywhere is impacted by the choices we make in the Global North, not just the “environment” we see around us.

Part 1: Today the Rivers Run Red

Made in Indonesia:

The Citarum River has its headwaters on the volcano Mount Wayang on the island of Java, where it sources and flows pure enough to drink from. Initiating as a small stream, it eventually broadens as it reaches the lower lying villages of Java. It is a source of water and hydroelectric power for millions of Indonesians. It travels for hundreds of miles as it makes its way down from the mountains, gradually evolving from a river pristine and fresh, to something otherwise.

Along the lower reaches there are hundreds of textile mills, and toxic wastewater discharged into the river is red, blue, black, or green on different days of the week, depending on what dyes have been used. Less apparent are the heavy metals accumulating in the river, including zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn), and iron (Fe). To avoid detection, factory effluent is sometimes discharged into the river at night or via underground pipes. According to DW Documentary, around 500 textile mills send their effluent directly into the river, with roughly 340 gallons of wastewater produced daily. River water that is perpetually colored becomes opaque, preventing light from penetrating through the water. Carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen disulphide (H2S) dissolved in effluent displace river water oxygen, and in many reaches, the Citarum River is effectively dead.

Much of what is produced in this region is polyester fabric, which is the source material for much of what we put on our bodies when we head out to the roads and trails. In fact, 54% of all fiber produced globally is polyester. In one facility, 1000 machines operate 24-7 to produce 9.8 million feet of spooled polyester fabric per month. While this fabric is supplied to various athletic and fast fashion brands across the world, including the U.S., the sheer volume of what is produced in just this one mill speaks to our heavy dependence on polyester fabric, whether for getting outside or just getting dressed in the morning. Surrounding villages bear the burden of this heavy dependence, with residents suffering from skin disorders and gastrointestinal distress because the Citarum River is their only source of water for drinking, washing, bathing, and irrigating their fields. The children are especially vulnerable and tend to fall ill more frequently.

Made in India:

Because polyester fiber is sourced from plastics (i.e. petroleum) and widely recognized as a “nonsustainable” fabric, some companies have increased manufacturing of more “environmentally-friendly” textiles, including those made from organic cotton, lyocell, modal, bamboo, and viscose. Lyocell, modal, bamboo, and viscose are cellulosic fibers and require the use of noxious chemicals to convert from solid wood into a fiber (Cline, 2013). They are sourced from tree plantations that have replaced rainforests in many countries, including Indonesia. Every year, thousands of hectares of rainforests are cleared to make room for these plantations.

According to Fast Fashion – The Shady World of Cheap Clothing, a viscose factory in Nagda, India, first mixes the wood chips with carbon disulfide (CS2). This mixture is then immersed in a solution of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and ultimately pushed through an extruder to form the fiber strands (Cline, 2013). Upon contact with the sulfuric acid, the carbon disulfide vaporizes into the air, which is incredibly toxic for factory workers and surrounding villages. Heart attacks and neurological disorders are not uncommon. North of Nagda along the Chambal River, in a village called Parmarkhedi, villagers suffer from paralysis and speech disorders. According to the villagers, the viscose manufacturer has been dumping effluent into the Chambal River for decades, resulting in these illnesses downstream. Villagers depend on the river water for drinking, washing, and irrigating their fields. Of the afflicted, there are children who were born healthy but over a period of years, have become physically disabled to the extent that they are now wheelchair-bound. And there are three siblings in their 20s who suffer physical disabilities from years of consuming the tainted river water. They no longer speak and the girl has fully greyed. They simply look lost, their eyes hollow. I struggle to believe that there is hope for them.

Made in China:

The Li River has its headwaters in the Mao’er Mountains in South China. Initially flowing clean, it merges downstream with the Pearl River, and there, the system becomes more polluted as a result of textile effluent dumped into the river. Around these mills and factories, many villagers suffer from gastrointestinal cancer and other illnesses, as a result of consuming tainted water. Importantly, 41% of our clothing is now manufactured in China (Cline, 2013) and the use of coal to power many Chinese factories results in significant carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. In many areas, the air quality is poor.

Ma Jun, Director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE) helped develop the Global Business Accountability map, which can be used to show the global supply chain originating in China. Have a look…recognize any brands? In the RiverBlue Documentary, Ma Jun explains that in China, textile factories and mills discharge 2.5 billion tons of effluent into the rivers each year. Workers, villagers, and aquatic life all suffer as a result. Tianjie Ma, Toxics Campaigner, has worked with Greenpeace to discover that many of the carcinogens present can be traced back to textile dyes in effluent released into the river water, particularly the azo dyes, which are banned in Europe and North America. Other nasty chemicals identified through testing include hormone disruptors powerful enough to change the gender of a fish, organotin compounds, perfluorinated chemicals, chlorobenzenes, chlorinated solvents, and heavy metals such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg). Some of these chemicals have been found as far away as the Canadian Arctic, in the body of an unsuspecting polar bear.

Orsola de Castro, a sustainable fashion designer interviewed in the documentary, says that in China, the local villagers can predict the “it” color for the upcoming season, based on the colors that are predominately flowing through the rivers. Moreover, the physical bodies of textile dyers become permanently colored to the extent that you can determine from appearance alone, which dyes they work mostly with. Entire bodies are stained yellow, red, blue, or green, including their saliva.

This is inhumane.

But here in the Global North, we place a demand for a textile product every time we purchase a new running shirt or pair of shorts, particularly the extras that we don’t need. Emphasis here on DON’T need…I am not here to discourage anyone from purchasing items that are necessary or even the ones that are really wanted. But let’s be honest…how many of these are impulse purchases, based on ads or an image on social media that caught our eye? It’s something to think about. We can do better.

The reality is, the majority of consumers in the Global North are unaware of any of this. While factory working conditions have been brought to light in recent decades, details of the environmental destruction resulting from the textile industry have remained elusive, and modern consumerism is accelerating this at an unprecedented scale. Very few consumers even know that not all the fabric going into a factory will come back out – offcuts are the trimmings left behind after manufacturing of garments and alone make up 15% of textile waste. Then there are the defective items, the factory “seconds” and “thirds”… No, fashion can’t and won’t save the planet. And no, there’s no such thing as sustainable clothing, other than the clothing you already have in your closet. Only buy when you actually need something and use everything until the bitter end, regardless of all the ways in which a social media post or retail advertisement tries to influence you.

The sad truth is that, in many cases, textile effluent is not treated prior to discharge into the rivers in an effort by factories and mills to minimize any “unnecessary” costs. Additional costs incurred by mills and factories would be passed on to the brands, and as a result, many operators fear that brands might pull their contracts from these factories and mills to partner with others. One textile worker at an Indonesian facility has opted instead to use the more economical “itchy hand” test: if he pours the discolored effluent over his hands and they don’t get itchy, then it’s all good.

This is the state of global textile manufacturing.

According to Ma Jun, “…when China is providing the whole world with all those clothing [sic], at the same time, we are suffering all the pollution that is left behind…every single piece of clothing you buy comes with a cost.”

He’s really not joking.

Made in the U.S.A.:

Throughout the 1980s, retailers began to tap into the booming overseas textile manufacturing markets, to take advantage of lower labor costs. After NAFTA was enacted in 1994, more manufacturing jobs were moved to Mexico, accelerating the push for cheaper products produced by lower wages that could only be produced in such a manner throughout the Global South. In 2000, the U.S. still produced 50% of our clothing, but as of 2013, we manufactured just 2% of our clothing (Cline, 2013). Today, very few brands, such as American Giant, have supply chains that are based entirely in the U.S., from the fields growing the cotton to the factory sewing the material into a t-shirt or hoodie. For other brands that are “Made in the U.S.A.,” supply chains may still be global. For example, Royal Apparel products are made in the U.S.A. but materials are made from both domestic and imported fibers. And because the state of the textile industry has driven down wages everywhere, even some U.S. factories, such as those manufacturing in Los Angeles, for example, barely pay their sewing machine operators the minimum wage. Ironically, sewing machine operators cannot afford to buy the clothes they sew 10 hours a day, six days a week (Cline, 2013).

So many race shirts…

According to Trees Not Tees, every year millions of race shirts are given away that are never actually worn. The majority of race shirts are made from polyester material, and that’s A LOT of polyester. So here’s a little math… To produce 2.2 lbs of polyester, you’ll need about 4.5 gallons of water. So, one pound of fabric calls for about 2 gallons of water. Based on those numbers, to produce a single polyester race shirt like mine weighing 3.5 oz, you’ll need 0.43 gallons of water. Multiply that by the estimated one million shirts given away and unworn each year, and that equates to 428,571 gallons of water wasted each year. And don’t forget about the 70 million barrels of oil used in that year to produce polyester fabric (Muthu, 2020). Cotton shirts are even more water-intensive. According to National Geographic, it takes more than 600 gallons of water to make just ONE of my cotton t-shirts. That’s about what I might drink over the course of 2.5 years.

Producing shirts made from recycled polyester may cut energy use by 62%, water use by 99%, and CO2 emissions by as much as 20%. That said, plastic bottles can continually be recycled into more plastic bottles, whereas polyester clothing made from recycled plastics can no longer be recycled at the end of its life. Regardless, the amount of all textile recycling remains low, with currently only 14% of new polyester clothing being manufactured from recycled polyester. Fabrics made from blended fibers, such as those used in some of my favorite cotton/polyester t-shirts, are not recyclable because the fibers cannot be separated (Cline, 2013).

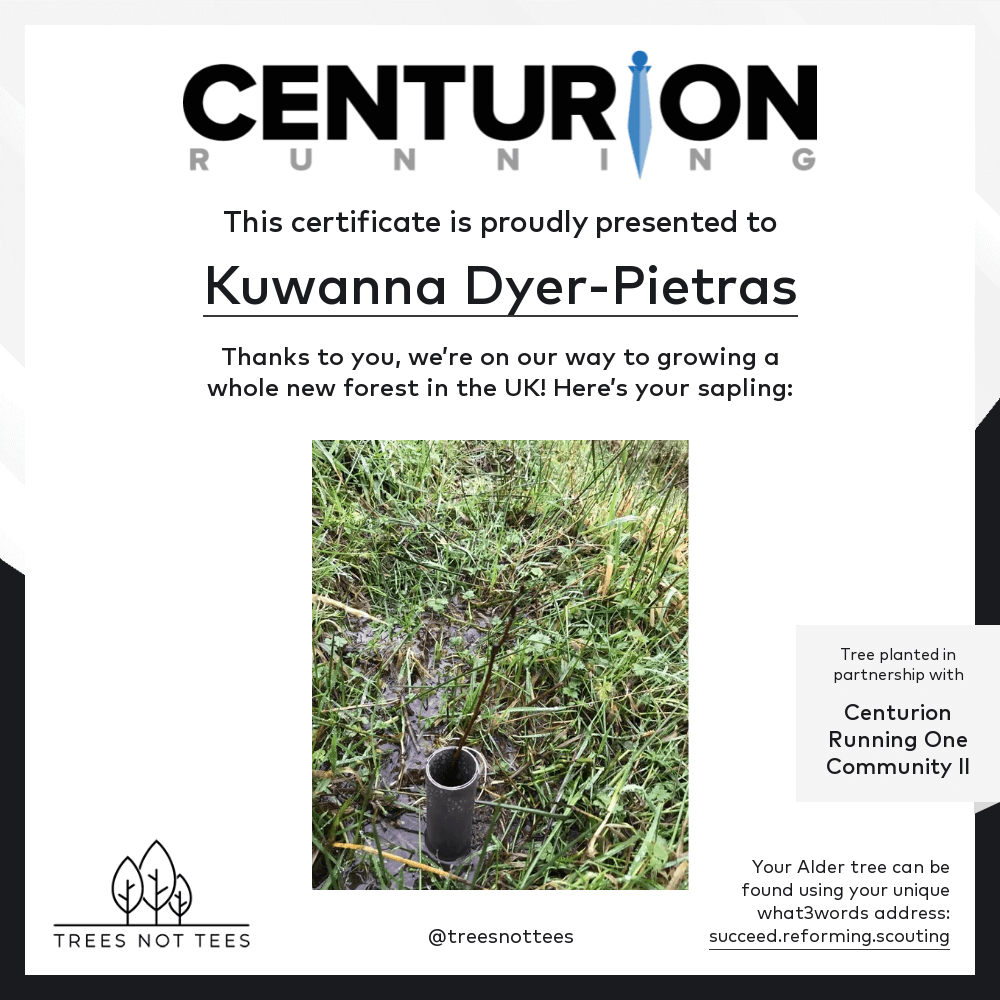

In an effort to help decrease the number of unwanted race shirts going into landfills, organizations like Trees Not Tees partner with race directors, so that race participants may have the option to have a tree planted in lieu of receiving a race shirt. During the pandemic, I participated in a virtual Centurion Running event and had a tree planted in my name. It felt great then and even now, knowing that there is a sapling in a Scotland forest growing in my name, simply because I opted out of a race shirt I didn’t need anyway. Recently, Trees Not Tees announced a partnership with the IRONMAN group for all their 2023 events. And Trees Not Tees has also worked with ReRun Clothing, whose founders Dan and Charlotte operated a second-hand running gear shop in Brighton, England for several years. In a 2018 interview with Runner’s World, Dan stated that about 60% of their donations were race finishers shirts, many still with their tags or original packaging. He explained that the plastic in each race shirt is equivalent to 8-9 plastic bottles, so these shirts pollute in the same way as the water bottles they are made from…only without the stigma. Dan and Charlotte’s shop quickly filled with donated clothing and shoes, and they resold what they could, donating the profits, all the while asking the question, “But do you really need it?”

Some race directors, such as Mathias Eichler, director of Rock Candy Running in Washington state, have for the most part, eschewed race shirts completely. I reached out to Mathias to better understand his philosophy on race swag. He was able to elaborate on his general view of swag and our culture of overconsumption and expectations, even in races, reminding all of us that “If you sign up to run a race, you don’t pay for a swag bag with lots of useless trinkets, you pay to participate in an adventure in the outdoors.” And don’t we? In 2022, for every Rock Candy Running race bib handed out in lieu of race shirts, $1.00 was donated to plant a tree to aid in forest fire recovery and otherwise. As a result, last year Rock Candy Running was able to help facilitate the planting of 200 trees. With 200 trees in the ground there are 200 fewer race shirts in circulation. And with 62% of American textile waste landfilled each year, that means 124 shirts were potentially saved from a landfill. This is just one race organization…imagine what we could do if more race directors and organizations followed his lead.

Other approaches adopted by some race directors include using higher quality and responsibly-sourced shirts produced by companies such as Patagonia and Royal Apparel, to at least increase the likelihood that shirts will be worn and loved. Other race directors will make race shirts completely optional, also helping ensure that a greater percentage of runners actually wanting shirts are the ones who end up with them.

How about all our running shoes?

Other than a running bra for some of us, running shoes may arguably be the most essential piece of gear in which we invest. And with an estimated shelf life of 300-800 miles, at some point your running shoes will need to be retired and you’ll move on to the next pair. The more miles you run, the faster you retire your shoes. In 2021, the global athletic footwear market was valued at $127.3 billion and is expected to exceed $196.1 billion by 2030. Key trends believed to be responsible for this growth include increasing popularity of sports and fitness, growth of e-commerce, and rising levels of consumer disposable income. An explosion in the popularity of trail and ultrarunning in recent years has, no doubt, contributed to this incredible growth. So what becomes of the old shoes, and how are the new ones even manufactured?

Today’s athletic shoes are composed of various plastics, including several phthalates, polyurethane, polyamide, polyester, nylon, and vinyl. As a result, athletic shoes are difficult to recycle, and most are donated or trashed at the end of their lives (National Geographic). Biofabrication and 3D-printing offer some hope for the future, as well as other innovative products, such as the Adidas Futurecraft Loop, in which shoe soles and uppers are constructed from the same materials, in this case, recycled ocean plastics. These shoes reaching the end of life are ground up, recycled, and then re-manufactured into new pairs of shoes, though there may be a limit as to how many times this process can be repeated. At a high price point, the shoe also may not be viewed as a financially-viable option for many runners. Asics is also working on footwear that improves the circularity of their products, using the equivalent of 25,000 polyester shirts (five tons of recycled textile waste) to manufacture shoes. Their process also utilizes solution dyeing, which reduces CO2 emissions by 45% and water use by 33%. As of 2013, Puma had developed their InCycle line, which is Cradle-to-Cradle-certified and includes clothing and shoes that are biodegradable or recyclable (Cline, 2013). NNormal, a brand recently founded by Kilian Jornet in partnership with the footwear company Camper, also seeks to improve the circularity of shoes and clothing through their No Trace Program. On their website, the company solicits athletes to donate their used gear to the company, so that the gear may be repaired, recycled, or in some other manner kept out of a landfill. I reached out to the company to get more specifics about their program but have not yet heard back.

Manufacturing the majority of athletic shoes is definitely not a green or sustainable process, with the use of several different plastics and other synthetic materials, as well as large CO2 emissions resulting from the use of coal in factories in China, where many of our shoes are also made. According to a study conducted by MIT in 2013, a pair of running shoes generates about 30 lbs of CO2 emissions. Many shoes that are donated end up in the global secondhand textiles market; some are simply too worn to wear and are landfilled if no one buys them. In other cases, they may be burned as a heat source, though doing so is not exactly legal and releases chemicals into the air, significantly degrading the air quality of homes and towns.

Part 2: “Earth is Our Only Shareholder” ~Patagonia

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR):

According to Harvard Business School, in previous years, businesses actively focused on maximizing their profits, whereas today they also have a social responsibility. This responsibility to society centers around environment, ethics, philanthropy, and economy. Each year many companies publish a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) report to communicate their social responsibility initiatives over the past year and the resulting impact on environment and community. While the intent is to be more transparent to their customers, not all brands may take it seriously enough, and with many factory audits announced well ahead of time, factories have plenty of time to “prepare” for the auditors’ arrival. Improvements in factory buildings and wages also tend to fall on the factory operators, who are told by the retailers that they must incur the additional costs, and many of these factories also subcontract to other factories, whose working conditions remain a mystery (Cline, 2013).

Back in 2011, The North Face published its first CSR report, and other companies such as RAB and Lowe Alpine, Fenix Outdoor have also published CSR reports. REI published something similar for their initiatives in 2021 and Columbia Sportswear Company has reports from 2020 and 2021. Nike, Inc. has published several impact reports. I was unable to locate a CSR report for Patagonia, though they have issued a generalized statement of their position on corporate responsibility here and their history of environmental and social responsibility here.

Though perhaps a little less transparent, Patagonia has set an example for circularity in the industry since 2005, when they started their Common Threads Garment Recycling Program, which sought to recycle the used polyester baselayers no longer needed by their customers. Eventually in 2011 this program became the Common Threads Initiative, which existed as an eBay store where Patagonia customers could sell and buy used clothing and gear. And in 2013 it became Worn Wear, originally operating from Patagonia stores but also moving online by 2017.

According to a 2022 study by Toxic Free Future, a Seattle-based nonprofit, 72% of waterproof and stain-proof clothing and other products sold in the U.S. are made so through the use of PFAS (Schreder and Goldberg, 2022). On February 21, 2023, REI announced that it would begin phasing out PFAS from all clothing and cookware in their stores by the fall of next year, after lobbying by Toxic Free Future for the company to make these changes. (They are currently lobbying Dick’s Sporting Goods to do the same.) PFAS, which is short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are also referred to as “forever chemicals.” Aptly named, PFAS are shed from the clothing we wear outdoors and tend to linger in these environments because they do not break down. These are toxic chemicals that have been linked to cancer, liver damage, weakened immune systems, and other health problems. PFAS are also used in fire response and industry, and have been detected in waterways right here in the U.S. They have also been identified in some of the most remote locations on the planet, including Khumbu Glacier on Mt. Everest, where they were found to be present in all of the sampling locations in a recent study (Miner et al., 2021). Back in April 2022, the Natural Resources Defense Council gave REI an “F” score on its use of PFAS, based on promises that had been made in advance of PFAS still being detected in its clothing, as well as a lack of transparency by the company. The outdoor brand scoring highest was Patagonia, earning a “B”; the company has committed to phase out PFAS in all their products by 2024. Other company ratings and explanations can be viewed in the NRDC press release. The state of California is set to ban all use of PFAS starting in 2025.

Greenwashing:

Many companies are starting to recognize customers’ concerns regarding the impact that their business and manufacturing practices have on the environment. In response, some are making adjustments to lessen their footprint, while others are arm waving just a little more.

In the trail and ultrarunning world, we may sometimes believe that the “outdoor” brands are best for us when we’re out on the trails, and that because they manufacture products intended for wild places, they are somehow greener and more sustainable in both practice and intent. But this isn’t necessarily true. As it turns out, many, if not all clothing brands are contributing to some form of environmental degradation. Many, if not all are engaging in some form of resource depletion. And many, if not all have a pretty significant environmental footprint.

I recently came across an article regarding a recent campaign between two brands who couldn’t possibly be any different from one another. In the article, the author Em Hartova fearlessly asserts that, even amidst the uproar among outdoor purists, fashionistas, and execs congratulating each other, we’ve missed the point of how heavily we are already impacting this planet and draining its resources, without such a campaign that appears to have no significant purpose: Is it fashionable enough to wear to dinner with friends? Is it practical enough to wear hiking a 14-er? And how was any of it produced? But indeed, “…clothing is clothing, regardless of whether we call it ‘gear’ or ‘couture’.” It all has a footprint.

Another outdoor retailer has recently recognized that they, as well as other manufacturers of polyester clothing, are playing a role in the problem of microplastics entering our water systems and ultimately, the oceans. Each time we launder our polyester shirts, pants, and fleeces, we send microfibers into our waters (De Falco et al., 2019; Palaceos-Mateo et al., 2021), where they are consumed by fish and other marine life, to their detriment…and to ours. Remember that the next time you have seafood for dinner.

Moreover, in this article, they state that “The next big task will be to secure a living wage for all workers making [our] goods.” While I’m sure most of us are now aware that the majority of hands that produced our clothing did not receive living wages, I’m sure there are a few of us who might be surprised to know that the hands that sewed their Synchilla fleece also likely did not. But maybe this is not so surprising, given that sewing machine operators in the numerous factories throughout China are paid wages ranging from only $117-$147 per month, in the Dominican Republic around $150 per month, and in Bangladesh only $43 per month (Cline, 2013). And these are the sewing machine operators in factories contracted by all the retailers, large and small, indoor and outdoor.

Additionally, in 2011, the company discovered human trafficking in its Taiwan mills. Several of their second-tier textile mills are in Taiwan, and second-tier mills that weave and dye the fabrics are typically removed from the oversight of a brand. Most of the oversight occurs at the first tier – the factories producing the clothing – and likely why their COO at the time didn’t seem too surprised as he explained to the author of the article how they went into the audit not being naïve about what they might discover. Still, they do not own any of the factories they use as stated here, and U.S. retailers who do not own the factories manufacturing their products may not be legally liable for working conditions in those factories (Cline, 2013).

In 2019, this company and this one and this one, as well as numerous others, were accused of manufacturing clothing with cotton forcibly produced by the Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang, China (Xu et al., 2020). In 2021, this company and this one, as well as others, were accused of being linked to clothing produced by forced labor of the Uyghurs. I was unable to locate more recent updates to these stories, though I know clothing companies are quick to change suppliers when violations such as these are committed. And rightly so.

Here’s the reality: any large retailer that produces a lot of clothing is going to have some amount of negative impact on the local environment, and there will be missed human atrocities because it’s almost impossible to monitor every activity in all these facilities so many thousands of miles away. Many factories also subcontract to other factories, making it even more difficult to track all manufacturing activities (Cline, 2013). Regardless of marketing, regardless of greenwashing, and regardless of image, no outdoor retailer will magically be immune to the same issues facing their indoor counterparts.

Retailers simply need to manufacture less. And for that to happen, we need to buy less.

Part 3: Where Do Old Clothes Go To Die?

Secondhand Markets of the Global South:

When was the last time any of us really understood what happens to a running shirt or short that has reached its end of life (in our eyes), once we pass it on to a thrift store, turn around, and walk away? What exactly is “away”?

It turns out, “away” is a landfill here or East Africa and Ghana.

According to the EPA, Americans generate 16 million tons of textile waste each year and more than 60% of textiles are landfilled right here. 700,000 tons of used clothing is sent to other countries. Some of our waste is even dumped in the Gulf of Guinea (Okafor-Yarwood and Adewumi, 2020) or in the Chilean desert (Sparks, 2021). Perhaps this is exacerbated because on average, we wear a garment only 7 times before discarding it (Cline, 2013). Day after day, large cargo ships arrive at the coast of African countries such as Ghana, loaded with castoff clothing from secondhand markets originating in the Global North…i.e., that polyester tech shirt you passed along to the local thrift store last week. Most of the clothing that arrives is made of polyester and is a combination of fast fashion, slow fashion, and everything in between. But polyester fabric can’t be sold in the markets in Accra, Ghana’s capital, and the quality of most modern clothes is sub-par, and so after a lengthy travel from their western origins, 40% of the secondhand western clothing brought to the markets ends up landfilled there. Not biodegradable and loaded with chemicals, all this polyester clothing leaches toxins into the local groundwater, while fumes from the occasional methane fire fill the air. Not surprisingly, several U.S. brands have a high prevalence in the Ghana landfills.

Landfilling of the remaining 40% occurs only after market vendors spend money on elusive clothing bales, with no idea what quality of clothing is inside until after the bales have been opened and the money is spent. Sometimes the vendors are able to make a profit through resale of some of the garments. But all too often, the clothing is cheap, worn, stained, made of polyester, or a combination of these, and vendors take a loss, unable to sell much of what they took a risk on. Instead, they take a loss.

Though we imagine a fairy tale ending to our donated running gear to a local thrift store, presumably landing in the hands of a fellow runner on a more limited budget, the reality is that most of what we donate is landfilled here in the U.S. or sent overseas, and ultimately landfilled there. Using Goodwill as an example, about 5% of clothing donations are sent directly to a landfill, most commonly because of mildew. The rest of the clothing will sit on hangers for about four weeks (Cline, 2013) before being moved to Goodwill outlets, and what doesn’t sell at the outlets is then sent to Goodwill Auctions, where large bins of clothing and other goods are sold for a set price. Anything remaining after that may end up overseas. And according to Liz Ricketts, co-founder of the Or Foundation, a nonprofit founded to educate others on the secondhand markets in the Global South, your donated clothing may pass through hands in as many as four different countries, before arriving at its final destination.

In 2014, several East African countries imported more than $300 million in secondhand textiles from the U.S. and other western countries. In 2015, the East African Community (EAC), made up of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda, proposed banning all imported used clothing and shoes by 2019. The goal was to regenerate their own textile markets, which have dwindled over decades because of all the western imports. Unfortunately, under pressure from the U.S., all but Rwanda backed down and reduced their tariffs. Rwanda held firm but was suspended by the U.S. from preferential access to U.S. markets and some of its duty-free privileges on exports to the U.S. And so the secondhand markets in African countries continue.

Final Thoughts

Consumerism has penetrated every single aspect of society and even as trail runners, we are not immune to the push exerted by brands to purchase this shirt and that short, to upgrade this pack or that watch, or to update our perfectly adequate running gear to the latest line. I am unimpressed by a quarter-zip that says “Trail Wear” and even less impressed at the expectation that I should add yet another piece of running gear to my already more-than-adequate closet. If you wear it on the trail and it works for you, it’s trail wear.

We need to think more about where our clothing originates, the hands that produce them, and the local environment that bears the cost. We need to recognize how our purchasing decisions impact retailers’ business practices and the factories that depend on those businesses, particularly around safe working conditions and wages. If you demand too many things too cheap, too much of the time, ultimately it will show in the color of the rivers, the quality of your garments, and the low wages paid to garment workers to produce them.

And we need to stop believing that [outdoor] brands and their endless product lines are our gateway to the outdoors. The irony is that we’ve been taught to believe that endless consumerism of “outdoor” products is our only ticket to getting back to the outdoors. No clothing company is going to save the planet from the products of textile manufacturing by continuing to manufacture these products that degrade the environment in the first place (Robert Jackson Wood). Perhaps a moratorium on production is the answer.

She Definitely Said It Better

“The…campaign was able to provoke such strong reactions for the very same reason that has for years enabled outdoor clothing brands to stand aside whilst the remainder of the textile industry faced criticism for their practices: a vocal rejection of the notion of ‘fashion’. But clothing is clothing, regardless of whether we call it ‘gear’ or ‘couture’ – made by human hands, with resources taken from the earth. Shared love, or brands’ promise of it, feeds the lie that our time outdoors relies on material objects – that we need them, and without them would be bound to an unadventurous life indoors. How could we ever harm the thing we love – except to love it more. To climb higher, travel further, run faster – to never stop exploring. The pursuit of endless adventure, so often presented as the antithesis to a life caught up in the economic rat race, isn’t quite as innocent as being ‘at one with nature’. Just like the climbers summiting Everest, we all leave footprints – regardless of whether we think we’re leaving no trace. Our footprints are in the carbon emissions of our long-haul flights, the fluorocarbons leeching [sic] from our waterproof jackets, and in the dyes that flow from garment factories into rivers on the other side of the globe. Whilst we’re admiring the view in our outdoors, the clothes we’re wearing are breaking apart somebody else’s; it’s the ultimate greenwash.” –Em Hartova

“When I graduate, I don’t need a shirt. I need a planet.” –Liz Ricketts

References

- Eichler, Mathias, 2/26/23, personal communication

Research papers:

- De Falco, F., Di Pace, E., Cocca, M., Avella, M., 2019, The contribution of washing processes of synthetic clothes to microplastic pollution: Scientific Reports, v.9, p. 6633.

- Miner, K.R., Clifford, H., Taruscio, T., Potocki, M., Solomon, G., Ritari, M., Napper, I.E., Gajurel, A.P., Mayewski, P.A.., 2021, Deposition of PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ on Mt. Everest: The Science of the Total Environment, v. 759.

- Okafor-Yarwood, I. and Adewumi, I.J., 2020, Toxic waste dumping in the Global South as a form of environmental racism: Evidence from the Gulf of Guinea: African Studies, v. 79, no. 3, p. 285-304.

- Palacios-Mateo, C., van der Meer, Y., and Seide, G., 2021, Analysis of the polyester clothing value chain to identify key intervention points for sustainability: Environmental Sciences Europe, v. 33, no. 2, p. 1-25.

- Schreder, E. and Goldberg, M., 2022, Toxic Convenience: The hidden costs of forever chemicals in stain- and water-resistant products: Toxic-Free Future nonprofit.

- Xu, V.X., Cave, D., Leibold, J., Munro, K., and Ruser, N., 2020, Ugyurs for Sale: ‘Re-education’, forced labour and surveillance beyond Xinjiang: ASPI Policy Brief Report No. 26/2020.

Books:

- Cline, E.L., 2013, Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion: Portfolio/Penguin, 244p.

- Muthu, S.S. ed., 2020, Environmental footprints of recycled polyester, Springer Singapore, 99p.

Documentaries:

- A Plastic Ocean: https://aplasticocean.movie/

- The Environmental Disaster that is Fuelled by Used Clothes and Fast Fashion: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bB3kuuBPVys

- The World’s Most Polluted River: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEHOlmcJAEk

- RiverBlue Documentary: https://riverbluethemovie.eco/

- Fast Fashion Clothing – The Shady World of Cheap Clothing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhPPP_w3kNo

- How Your T-Shirt Can Make a Difference: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEExMcjSkwA

- The Truth Behind Fast Fashion – Are Fashion Retailers Honest With Their Customers?: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=23vUvQN-R1Y

- Your Sneakers Are Part of the Plastic Problem: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIgeM2JFIWo

Web articles:

- Assoune, A., The Truth About Recycled Polyester Fabric Sustainability: https://www.panaprium.com/blogs/i/recycled-polyester-fabric

- Browning, P., 2023, REI to stop selling clothes, cookware with ‘forever chemicals’: https://www.kuow.org/stories/rei-has-committed-to-phasing-out-pfas-toxins-aka-forever-chemicals-9fbf?ref=upstract.com

- Chu, J., 2013, Footwear’s (Carbon) Footprint, MIT News: https://news.mit.edu/2013/footwear-carbon-footprint-0522

- Goldberg, E., 2016, These African Countries Don’t Want Your Used Clothing Anymore: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/these-african-countries-dont-want-your-used-clothing-anymore_n_57cf19bce4b06a74c9f10dd6

- Hartova, E., 2021, How the North Face x Gucci controversy is Hiding the Real Issue: https://adventureuncovered.com/stories/how-the-north-face-x-gucci-controversy-is-hiding-the-real-issue/

- Langenheim, J., A scrap of difference: Why fashion offcuts don’t need to end up in landfill: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/partner-content-prada-renylon-ganzhou-china

- McGuire, J., 2018, Why ReRun Clothing want you to think twice about taking that finishers t-shirt: https://www.runnersworld.com/uk/gear/a776566/rerun-clothing/

- Porter, B., What Really Happens to Unwanted Clothes?: https://www.greenamerica.org/unraveling-fashion-industry/what-really-happens-unwanted-clothes

- Sparks, H., 2021, Chilean desert is site of 39,000 pounds of scrapped clothing: https://nypost.com/2021/11/09/chilean-desert-site-of-39000-pounds-of-scrapped-clothing/

- Stenzel, T., 2021, Asics Saves 25,000 T-shirts from Landfills to Create Recycled Sneakers: https://fashionunited.com/news/fashion/asics-saves-25-000-t-shirts-from-landfills-to-create-recycled-sneakers/2021041639486

- Stobierski, T., 2021, Types of Social Corporate Responsibility to Be Aware Of: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/types-of-corporate-social-responsibility

- Stokes, D., 2021, Nike, Patagonia Named in New European Criminal Filing for ‘Crimes Against Humanity’ in China: https://nationalpost.com/news/world/nike-patagonia-named-in-new-european-criminal-filing-for-crimes-against-humanity-in-china/wcm/cba7b698-176b-4f2a-95d2-af2de77d97d6/amp/

- Unglesbee, B., 2023, REI requires suppliers to phase out ‘forever chemicals’: https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/rei-pfas-suppliers-sustainability-climate/643538/

- White, G.B., 2015, All Your Clothes Are Made With Exploited Labor: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/06/patagonia-labor-clothing-factory-exploitation/394658/

- Wood, R.J., 2022, Patagonia’s Greenwashing Ignores Workers and Won’t Solve the Climate Crisis: https://truthout.org/articles/patagonias-greenwashing-ignores-workers-and-wont-solve-the-climate-crisis/

- A conversation with Liz Ricketts: https://www.fashiondenier.com/conversations/a-conversation-with-liz-ricketts

- New PFAS Scorecard for Popular Apparel Brands: Levi Strauss Earns an ‘A+’, Outdoor Brands Fail: https://www.nrdc.org/media/2022/220406

- Bangladesh factory collapse toll passes 1,000: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-22476774

- PFAS Contamination in the U.S. (June 8, 2022): https://www.ewg.org/interactive-maps/pfas_contamination/

- Adidas Unlocks a Circular Future for Sports with Futurecraft.loop: A Performance Running Shoe Made to Be Remade: https://news.adidas.com/running/adidas-unlocks-a-circular-future-for-sports-with-futurecraft.loop–a-performance-running-shoe-made-t/s/c2c22316-0c3e-4e7b-8c32-408ad3178865

- The 2025 Recycled Polyester Challenge was designed to accelerate change.: https://textileexchange.org/2025-recycled-polyester-challenge/

- Clothing and Pollution: https://www.theconsciouschallenge.org/ecologicalfootprintbibleoverview/clothing-pollution

- Athletic Footwear Market Growth & Trends: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-athletic-footwear-market

- Athletic Footwear Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Type (Running Shoes, Sports Shoes, Aerobic Shoes, Walking Shoes, Trekking & Hiking Shoes), By End User (Men, Women, Children), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2022 – 2030: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/athletic-footwear-market

- An Update on Microfiber Pollution: https://www.patagonia.com/stories/an-update-on-microfiber-pollution/story-31370.html

- Patagonia Clothing: Made Where? How? Why?: https://www.patagonia.com/stories/patagonia-clothing-made-where-how-why/story-18467.html

- Working With Factories: https://www.patagonia.com/our-footprint/working-with-factories.html

- Our Quest for Circularity: https://www.patagonia.com/stories/our-quest-for-circularity/story-96496.html

- Reality Check: Why some African countries don’t want charity clothes: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44951670

- REI Co-op Raises Bar for Companies Operating in Outdoor Industry: Releases New Product Standards for its 1,000+ Brand Partners to Advance Social and Environmental Practices: https://www.rei.com/newsroom/article/rei-co-op-raises-bar-for-companies-operating-in-outdoor-industry

- Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report, 2022: https://textileexchange.org/knowledge-center/reports/preferred-fiber-and-materials/

Websites:

- Trees Not Tees: https://treesnottees.com/

- The Or Foundation: https://theor.org/

- Cradle-to-Cradle®: https://c2ccertified.org/

- Patches of Pink: https://patchesofpink.com/sewing-tools/your-question-how-much-water-does-it-take-to-make-one-shirt.html

- ReRun Clothing: https://rerunclothing.org/

- Patagonia: https://www.patagonia.com/factories-farms-mills/

- Patagonia: https://wornwear.patagonia.com/

- Environmental Protection Agency: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data

- IPE Global Supply Chain Map: http://wwwen.ipe.org.cn/MapSCMBrand/BrandMap.aspx?q=6

- Sources of PFAS: https://deq.utah.gov/pollutants/sources-of-pfas

CSR reports:

- Columbia Sportswear Company: https://investor.columbia.com/corporate-governance/corporate-responsibility-documents

- Fenix Outdoor: https://www.responsibilityreports.com/HostedData/ResponsibilityReports/PDF/fenix-outdoor_2021.pdf

- Nike, Inc.: https://about.nike.com/en/newsroom/reports/fy21-nike-inc-impact-report-2

- Patagonia: https://www.patagonia.com/corporate-responsibility-body.html

- Patagonia: https://www.patagonia.com/our-footprint/corporate-social-responsibility-history.html

- Rab and Lowe Alpine: https://rab.equipment/media/documents/Rab_and_Lowe_Alpine_Sustainability_Report_2021.pdf

- REI: https://www.rei.com/stewardship

- The North Face: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/north-faces-first-csr-report-reveals-green-goals-early-progress

Comments

Add Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Luke MacDonald

Great article, certainly feel guilty as charged. As a running & ski shop owner we do our best to offset as much as possible. We certainly would be convicted of greenwashing, however, we do believe in continual improvement and we have designed programs and project partners that are helping us become more sustainable. Your article is a thoughtful overview and provides us with some insights on how to proceed. #WorldLitterRun #FitItForward #UbuntuAward2010 #Pencils4Plastics #Data4Data #SnookieSocks #AerobicsFirst #OneLove

Kuwanna Dyer-Pietras

Hi Luke! I appreciate you reading the whole article and leaving a comment. I’m glad you find the article useful. I believe many of us are guilty as charged…but so, so many simply remain unaware of the extent of the problem. Most of the environmental damage that results from western demands remains invisible to us because it’s not in our own backyards. I think the key now is spreading awareness, but not just around “sustainability” in the usual sense of more recycled polyester and more organic cotton saving the world, but rather shifting away from a consumer mindset to one in which we buy only what we need and use it until it is no more. And brands need to stop producing so much. (Patagonia is at the forefront of using recycled fibers in their products, not to mention having a store entirely devoted to their own reclaimed gear, yet at every thrift store, both online and brick-and-mortar, you will find excess Patagonia gear. So even they should consider scaling back production.) Yours is a valuable resource, being a locally-owned store, and the kind we should frequenting when we do need that new set of ski tights or running jacket, and thrifting is not an option. So I appreciate you not only for taking the time to read and respond, but also for being a resource in your community of athletes. (P.S. I lived in Canada for a few years and loved it there. Beautiful country.) Be well!